Have you ever heard the phrase The “Elephant in the room?”

This phrase is usually used to communicate an issue, topic, or controversial subject, that everyone knows about but hardly anyone wants to talk about or discuss, at least in a civil and respectful manner.

This phrase may have originated with an 1814 fable in which a man in a museum notices every little detail in the museum except the giant elephant in the middle of the museum.

With that in mind, let’s ask ourselves a critical question. Why is it so difficult to talk about difficult subjects AND why does it often seem so for Christians?

To be honest it almost seems as though being a Christian makes it even more difficult to talk about difficult or controversial subjects.

In my opinion which includes years as a pastor and scholar, it seems we are far more comfortable talking about people who differ from us than we are competent at talking with people who are different from us.

The Ox In The Room

Proverbs 14:4 NLT “Where no oxen are, the manger is clean but much revenue comes By the strength of the ox.”

There a a few important things I learned while studying this rather obscure verse.

Apparently the ox is held in high esteem in ancient Hebrew culture.A large part of the economy depended on the ox. They were rarely sacrificed as offerings.

There was a strict Jewish code that commanded that oxen be protected and provided for.

The ox was also given a Sabbath just like their owners.

Revenue translated here isn’t really about money. It was most often also translated as “wisdom”

In other words nothing grows and no one benefits from avoiding keeping oxen in the stalls. There is no wisdom to be gained by avoiding the potential mess of talking about controversial topics. No one grows. And absolutely no one profits from silence.

I have a theory that Western Christianity has actually rendered us incompetent at discussing controversial issues with peoples whose opinions often strongly contradict our own views.

One of the reasons I believe to be true is because over several decades, and even more so in recent history, we in some cases subconsciously and in other cases consciously subscribed to the false narrative that knowledge can not transcend context.

In other words, truth, which we believe to be fixed and concrete, is only true when it comes from our context and particular community.

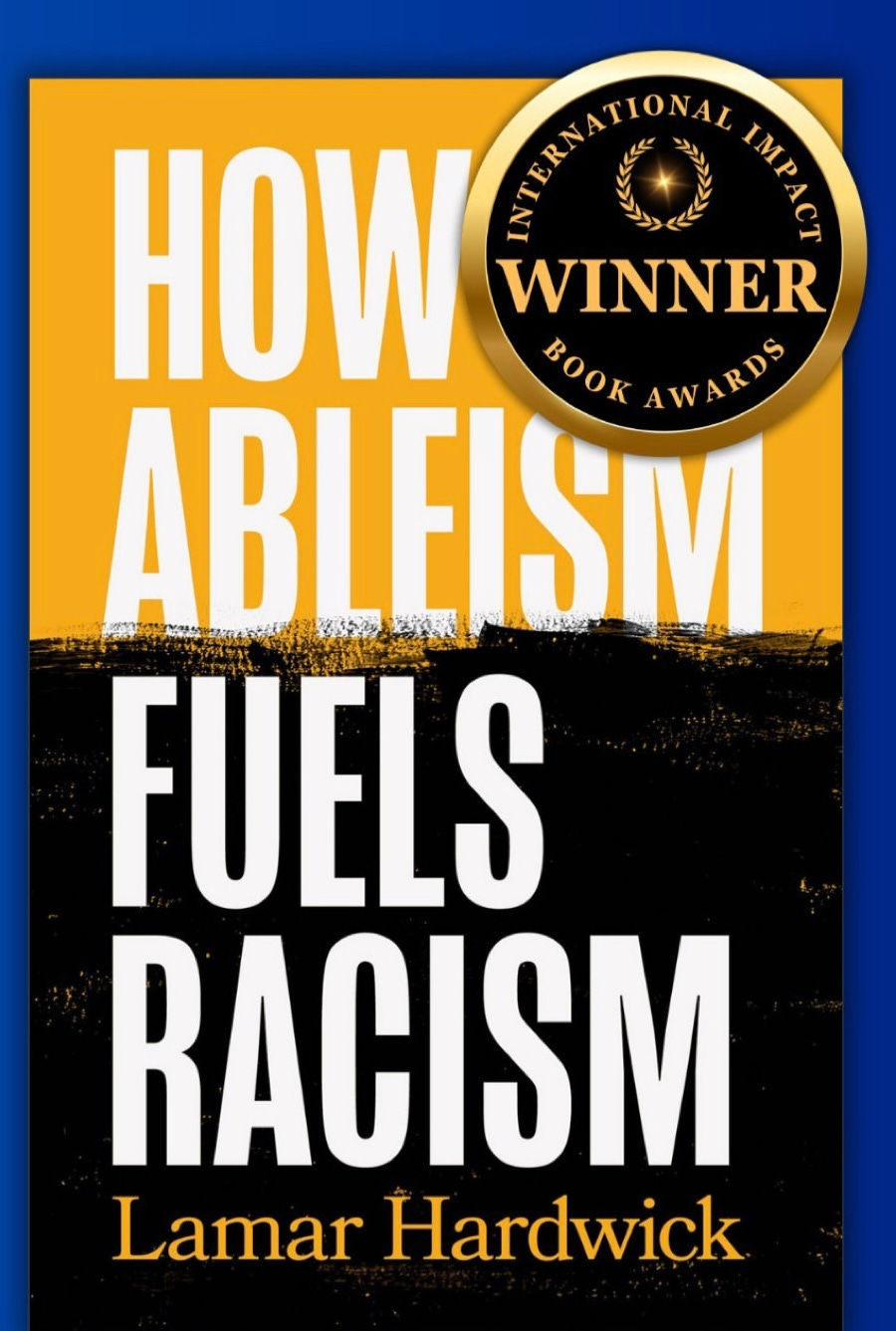

I actually write about an aspect of this is my most recent book, but that is not the primary reason for this post, so I’ll stick to the main thing here.

And that is this, when truth becomes an attribute that can be owned by a community that sees itself as not only the owners but the guardians of truth, persuasion no longer becomes possible in fact it becomes immoral.

Why is persuasion an important value? Because it allows for the open handedness and open heartedness that is critical to the empathy, growth, and civility that is a necessary ingredient for national unity. When persuasion is no longer an option, power fills the vacuum.

“If society rejects influence only power remains.”- Andrew T. Le Peau

I think we have an unhealthy relationship with the idea of persuasion. We don’t like it. We don’t trust it. So we demonize it. The problem is that what often results is a false sense of sanctity, peace, and unity.

We thought we were trading in the unethical and unchristian idea of persuasion for peace, the type of peace that comes from refusing to listen to ideas or reports of experiences that are not a normative part of the experiences of our group. After all, our group owns truths anything that doesn’t align with our beliefs, values, and more importantly our experiences, remain untrue and untrustworthy.

Refusing to listen is our way of fostering peace. But instead of fostering peace we’ve created a hunger to be heard that has given birth to an anger that is intense and in many ways justified.

The only way to reverse this is to learn how to handle difficult conversations with people who felt unheard, under extreme pressure, and under valued.

So this post isn’t about telling people what to say. This post is about helping us all to be better at being able to handle having the proverbial ox in our stall. So here are a few tips for having hard conversations of the next several weeks, taken from Andrew T. Le Peau’s book Write Better.

Respect the truth as best as we can know it and speak in a way that reflects it. Use credible information and sources. If your source always confirms your perspective or always challenges your perspective, it’s probably biased.

Be truthful about contrary view points. Don’t misrepresent other perspectives.

Misrepresenting other perspectives creates the easiest path to knocking down their views.

Give credit where credit is due. Don’t claim ideas as your own. This helps us to avoid

romanticizing our own intellect. Don’t become a talking head using other’s talking

points. It’s lazy. Seek to learn about the issues you’re attempting to discuss.

Be careful in your use of logic. Correlation doesn’t mean causation. It’s a cleaver tool to discredit an idea but it is dishonest. If you want to help someone learn avoid generalizations, false analogies, demonizing opponents, and avoiding the central issue.

Show humility. Your careful research and good logic may still mean that you are wrong. Be a life-long learner. Be willing to allow your mind to be changed and to have your beliefs challenged.

Oxen are large messy animals that are difficult to deal with and even more difficult to clean up after, but not having them present means no growth, no progress, no revenue. It’s easy to avoid the tough topics because we don’t want to get “messy” but the truth is avoiding it may very well be costing us more than we can afford.

Remember to Listen well, communicate well, and love well. This is the way.

Pastor L

Season Two of The HardLee Typical Podcast is coming soon!

Excellent as always, Lamar

I think honest discussions tend to be influenced by the type of culture in which one is raised. Some value frank conversations, and some do not.

There are contexts in which the predisposition is to take offense or exhibit fragility towards a topic, even when the communication is measured and non-judgmental. There is the cultural prohibition against saying the quiet part out loud.

For example, regarding the election:

For vice president Harris, being Black and female was a primary factor in her defeat in a nation with patriarchal preference and xenophobic tendencies. This likely triggered White solidarity and afforded White privilege for Donald Trump, a man with lesser character attributes, with documented behaviors of lying, insulting, mistreating women, and engaging in criminal activity.

This is a discussion that would likely never occur within contexts where ignoring the elephant and the ox is always the priority, or in contexts where Black people never say anything that might be construed as divisive.

So we keep kicking the can down the street and unhelpful habits are never challenged.